René Girard XIII: The Glowing Screen Altar

The text below is an old draft of an excerpt from the book Catharses.

The turn of the twentieth century coincided with the collapse in legitimacy of previous religious and political ordering. The old gods were dead, to paraphrase Nietzsche, and nations began to lurch through various ideologies that would replace them. There were various forms of socialism, nationalisms, scientific and technological progress, eugenics, psychoanalysis, new mysticisms.

None of the new trends were able to prevent catastrophes of the two world wars, however, and the second half of the century slumped into even lower depths of existential despair. Many sages of the moment tried to give a new meaning to life through ever more convoluted philosophies that an ordinary person had no time nor desire to understand. Epistemology, logical positivism, neo-pragmatism, ordinary language philosophy - how could one ever have hoped that such convoluted constructs could become a common foundation for a society?

Social cohesion in post-WWII world was rescued by something entirely different: popular culture. It was television that enabled everyone to get on the same page, to find common points of reference, to unify around common and simple narratives. Old religion and old politics were still discredited; there was no going back to the Church as the main arbiter of meaning, nor was there going back to serfdom and sacred monarchy. Yet, the increasingly obscure ideologies were not catching on either. In contrast, popular entertainment was easy to grasp, it offered a clear distinction between good and evil, it was soothing, and it was inspiring.

Sometime in the early sixties, my grandfather brought in the first television set into his home, the first of his neighbours to do so. The glowing screen inspired a visceral emotional response in the family. Here was a miracle of technology that gave flesh to the claims of progress. It confirmed the modern man’s sense of superiority over all the generations of his ancestors. No prophet or sage, no king or conqueror of the ancient times could have dreamed of such a device; no genius of the past could have explained it if it had been placed in front of him. Yet there it was, purchased for the pleasure of my grandfather and his family.

The glowing screen provided tremendous reassurance. One no longer needed to spend nights in the dark, or by the hoary light of candles or paraffin lamps, chewing the cud of local gossip, retelling same old stories, or reading mute and heady books. There was the welcoming voice of show hosts, smiling and looking handsome and greeting the viewer with sweet pleasantries. TV shows featured models of beauty and respectability for the people. They were filled with song and joy. There were conversations that everyone could get passionate about and continue them with their friends and neighbours the next morning. Even when there was talk of conflict or war, the news anchors were reassuring; they told us that our leaders will surely handle it, they urged us to stick together and support great common causes, they told us that we can only succeed together and that each of us had a part to play.

The TV also brought great leaders right into our hearths. The president would address you personally, summarizing his struggles and triumphs, and imploring you to remain loyal. And lo and behold, the leader was a human just like you and I! He was our nice uncle or grandpa working hard and navigating the course of the nation with his great wisdom and virtue.

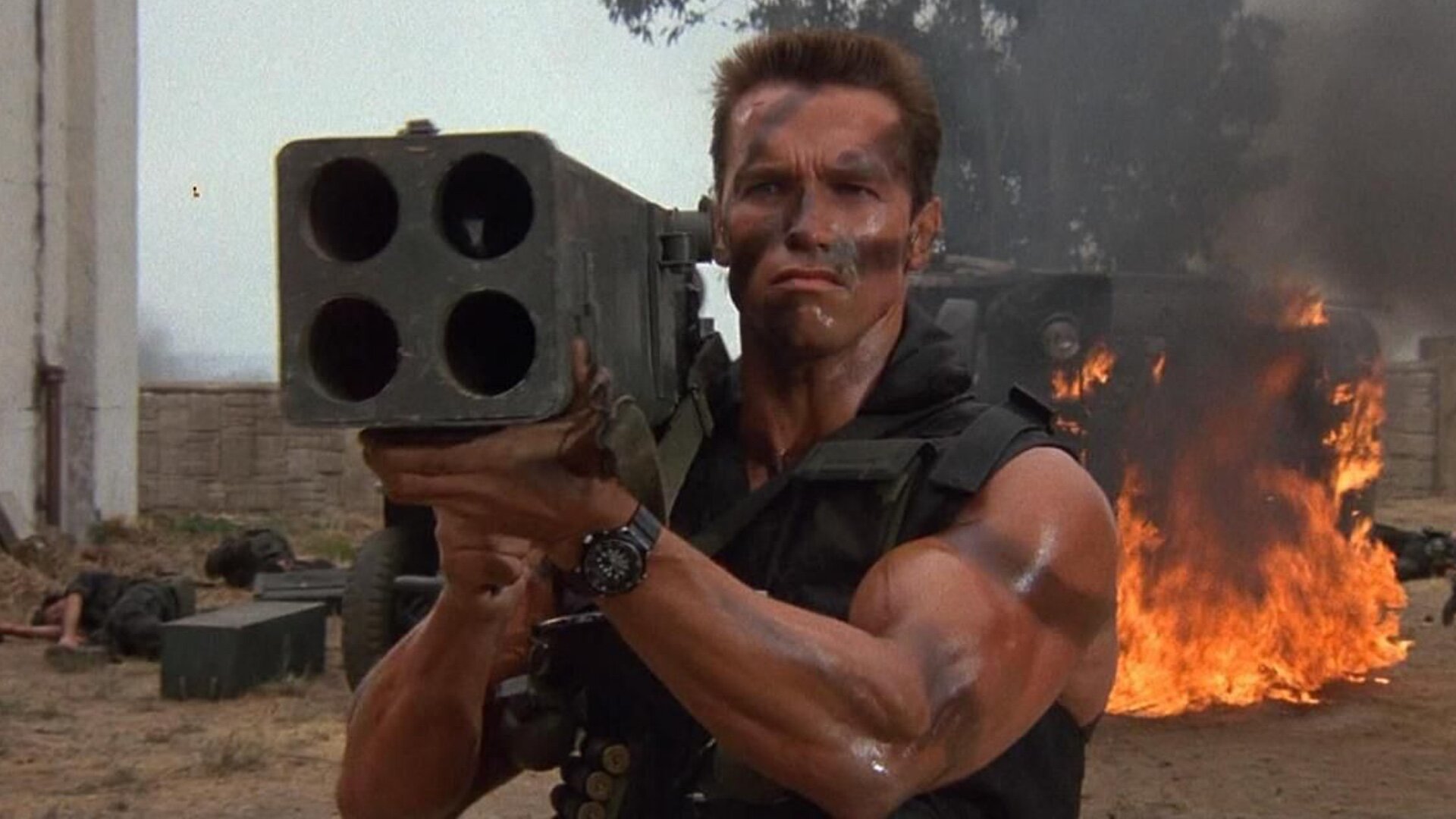

In film and TV series, we fell in love and adored the stars. We watched battles that we haven’t dreamed of before: cowboys, lawmen, spies, soldiers, lovers. Justice and beauty always prevailed, and evil was always expelled. Silver screen idols showed us the bright future: they showed us the clothes and the cars and the cities in which we will live, they showed us the principles we will hold, they showed us the technologies of a beautiful new age.

The screen also reinterpreted the old age for us. We watched stories of kings and pharaohs, of revolutionaries, of prophets, all brought right to our homes, resurrected and baptized as it were for this new age that the best of the ancients could perhaps intuit would come one day. And the best of them were just like us too, prefiguring the modern age, prefiguring America, which, if you think about it, was as though Hollywood was bringing America to the past, like Jesus brought the Gospel to the dead on Holy Saturday.

The intellectuals were brought out too, those silly sods. They would appear on debate shows where a charming everyman anchor would prod them about meanings of life, and they would go on lengthy expositions in front of a happy audience, who took a break from living the American Dream to dabble in philosophies and like esoteric curiosities.

During the breaks in great drama and shows, we watched merry ads, which suggested for us products that we could buy so that we can visibly participate in the great show that was the modern world. Consumption provided us with solid, tangible amulets for passing through the portal into modernity and connecting with the avatars on the TV screens, confirming to us that they are real and that we truly partake in a common community with them.

The evening television was brighter than the sunniest morning. The laughter and the chatter from the lo-fi TV set permeated the house and helped the ones who went early to bedroom to fall asleep. The overworked dad would simply pass out on the couch in front of the flickering TV screen.

In the rare moments when the TV set was off, one could hear the silence of the night outside the windows. You could hear a passing car or chirping of critters. You could feel the harrowing emptiness of the city as of the outer space. But you needed not face the emptiness; all you needed to do is turn the TV back on, and there were human faces, smiling and handsome faces, working at all times to expel the darkness.

The TV was the great altar for the modern age. It was so much more powerful than any altar anyone knew about that comparing it to altars is almost out of place, but not quite. In the archaic times it was the altar that gathered the community, it was in front of the altar that sacrifices were made, and evil was expunged, and it was at the altar that unifying narratives were received.

TV did all that, and how well! The Temple in Jerusalem at its peak, with its constant smoke rising up to please the nostrils of the Lord, was no match to the ceaseless flow of violence on TV screens. This was not the blood of goats and rams, but the blood of evildoers of every kind, and the ritual, rather than being an obscure incantation, was a finely crafted dramatic story, shot beautifully, and acted out convincingly. And it wasn’t even real blood! This was a great civilizational advance – bloodshed without bloodshed. They may have faked death in theatres in prior times, but that was nothing in comparison to the realism of film.

The ancients distinguished the healing blood of the sacrificial victims from the polluting blood of conflict. In Hollywood, the healing blood was dyed corn starch, and its cleansing power was tremendous. Animal blood became nothing; dead animals became nothing more than a nutritious source of protein.

Yet, despite its relative superiority, the TV altar inherited some weaknesses from the old altars. Namely, the polarizing and unifying power of sacrifice tends to attenuate. Thus, violent movies needed to get more and more violent, funny TV shows needed to become more cynical, sensual scenes had to become more explicit, music needed to become more and more rebellious. By the time we reached the end of the century, the older generation was profoundly disturbed by the sex, violence, and every other kind of intemperance that their children were consuming through mass entertainment. What happened to the Golden Age of Hollywood, they wondered, as Generation X shot heroin, listened to heavy metal or gangsta rap, and watched porn.

To the first generation of TV watchers, the new generations seemed to have forgotten all about the magic of TV to expel the night and unite the country. The new generation complained of television as an oppressive force telling them what to do, the omnipresent Big Brother trying to control their thoughts. Yet, this new generation was not casting away television. They were using TV to cast out TV, like Satan casteth out Satan. They inherited and adapted the TV, and they cramped up the dosage.

Sex, violence and intemperance were on television from the very beginning, from Gone with the Wind to Casablanca to John Wayne. The silver screen always showed and purged the dark recesses of human psyche. The principle was the same as that of tragedies of Ancient Greece, in which Oedipus commits patricide and incest and causes a plague, and is cast out of the city. The only thing that changed over the decades was the dosage, and this is only natural. Drugs need increased dosages to maintain equal effectiveness.

This type of sacrificial inflation is far from unprecedented. It is rather a common trope in the stories of decadence and fall of civilizations. Chesterton, in somewhat parochial language, explained that this was what happened to the pagan civilization of ancient Rome:

“There comes an hour in the afternoon when the child is tired of 'pretending'; when he is weary of being a robber or a Red Indian. It is then that he torments the cat. There comes a time in the routine of an ordered civilization when the man is tired at playing at mythology and pretending that a tree is a maiden or that the moon made love to a man. The effect of this staleness is the same everywhere; it is seen in all drug-taking and dram-drinking and every form of the tendency to increase the dose. Men seek stranger sins or more startling obscenities as stimulants to their jaded sense. They seek after mad oriental religions for the same reason. They try to stab their nerves to life, if it were with the knives of the priests of Baal. They are walking in their sleep and try to wake themselves up with nightmares.”

The most infamous sacrificial altar known to history, that of the human sacrifices of the Aztecs, is said to have swallowed up 80,000 victims in the course of four days in the fifteenth century. Surely, this must have been a peak of a long inflationary bubble, for the logistic complexity of that high a number alone would require long experience and advanced cultural organisation.

The conventional view on the matter is, in sum, that as a society grows stale somehow, the stimuli provided by every form of ritual need to be increased to keep the people contented, to help them go to sleep. To hear it from René Girard:

“The torture of a victim transforms the dangerous crowd into a public of ancient theater or of modern film, as captivated by the bloody spectacle as our contemporaries are by the horrors of Hollywood. When the spectators are satiated with that violence that Aristotle calls "cathartic" -- whether real or imaginary it matters little -- they all return peaceably to their homes to sleep the sleep of the just.”

Yet it is not only mere physiological saturation that causes sacrifices to lose power. Girard puts forward two key conditions for effectiveness of sacrifice. First, people must believe in the mystical power of the ritual. The degree to which they wake up, so to speak, to the theatricality of it, is the degree to which they cease to be enthralled. Secondly, the violence must be experienced as unanimous, representing the entire community against a single outsider. Once the sacrificial priests are no longer seen as performing the rituals humbly and piously, the violence they perpetrate on the altar is seen as a power move. Rather than honouring the gods, they are playing gods. This engenders reciprocal violence that rituals were originally meant to eliminate.

The Golden Age of Hollywood is the time when the conditions for effective sacrifice were fulfilled. It was the age when the negative stimuli were minimal, when audiences were unanimously sided with the good guys, and when Hollywood was identified with America. Things began to spoil as these perceptions faded. Sex and violence ramped up, antiheroes began to show up, and Hollywood became associated with a political agenda. The age of innocence was over.

As media became a play for power, rivals in media emerged. One news station represented the liberal view and another the conservative view. Chauvinist actors and directors separated from pacifist ones. New music became an act of rebellion against old music. The unifying altar of the silver screen began to crack.

Who knows how TV would have evolved had it not been for the rise of the Internet? Although, the Internet arguably was the evolution of TV, despite the fact that it featured viewer participation, the feature that one could argue makes the Internet an altogether separate line of species. One way or another, Internet irreversibly smashed the unifying power of popular media.

In the twenty first century, so far, popular media has made a complete hundred and eighty-degree turn. It no longer unifies, but divides. It is no longer a means for promoting peace, but a weapon for waging war. In Girardian terms, it no longer generates sacrificial violence, but reciprocal violence.

That the old trajectory of television has been broken is curiously attested, among other things, in the current drop in appetite for theatrical sex, drugs, and violence. The newest generation of audiences brings a sharp rise in conservatism when it comes to these stimuli. This is because the fictional victims of old media have been torn apart and immolated to the very end. The new victims from now on are not fictional. They are not even outsiders. The new victims of social media are one’s fellow citizens. And as far as they are concerned, the real violence has not even begun yet. We are at the stage of political bickering, echo chambers, and riots. Smashing a real window is more stimulating than watching one fake soldier fake-torture another fake soldier. There is a long arch of violence to traverse from here.

We are living in a time of a great transition, and we don’t know how things will settle. All unifying altars have collapsed. Out of blind habit, the powers that be are using old methods in an attempt to create cohesion: they are resorting to media. They are shouting from the rooftops that are the news outlets and TV stations and, nowadays, streaming services. But by doing so they are merely fuelling the flames of discord, for the platforms that once unified the masses are now the places with unprecedented power to divide. What will be the unifying altars of the future? It is anyone’s guess. If we cannot come up with any, well then, according to René Girard at least, we are entering the Apocalypse.

Read more in the book Catharses.