René Girard XV: Nerds

The text below is an old draft of an excerpt from the book Catharses.

René Girard has often complained about the reluctance of the academia to accept or even consider his work. The cold shoulder may be due to the usual envy of a competitor’s overwhelming success, or Girard’s transgression of borders of several disciplines, or, as I have held before, his seeming attempt to reduce the entirety of human experience to a single principle – mimesis. All of these motives can confront any intellectual with a breakthrough idea. Girard, however, has argued that there is something specific about his theory that makes it repellent not just to intellectuals but to everyone else.

Mimetic theory deflates the sense of moral, intellectual, or any other superiority we construct for ourselves, and which we necessarily contrast relative to our enemies because superiority must always be relative. In arguing that conflict turns adversaries into twins whose resemblance increases as their mutual hatred progresses, Girard swipes the rug from under anyone who would plant their feet firmly in confrontation against “evil”. There has always been a common intuition that resemblance produces rivalries, but Girard gives it a rigorous theoretical foundation that brings it into the fighting arena of theories, no longer dismissible as a sort of effeminate, wishful attempt to make peace.

In its rather irritating propensity to undermine our attempts to get on the right side of conflicts, Girard’s theory resembles Christianity, a religion famous, or infamous, for teaching us to turn the other cheek, love our enemies, or not to talk about specks in eyes of neighbours. Indeed, it resembles every religion in as much it argues against reliance on what can be called an internal moral compass. Girard acknowledged this, and he saw much of his work as affirming the Biblical tradition culminating in Jesus Christ.

Yet, to modern readers, rational and suspicious of organized monotheism, Girard’s writings offer an improvement over conventional religious preaching. They present a scientific argument, which is to say an argument based on logic and evidence, requiring no articles of faith and entirely devoid of insufferable moralizing and fear-mongering widespread among members of the priestly class. Girard has distanced himself from what he termed sacrificial Christianity, which, like the rest of culture, is based on immolating a victim, and in the case of sacrificial Christianity specifically, on consigning his soul to hell.

Modern academia largely defines itself in contrast to religion, but it shares with it more than it is willing to admit. To see that, consider the genealogy of academia as argued by Girard, though somewhat tangentially as far as I know. Civilization starts with the scapegoating mechanism, and all institutions trace their origin to it. What started as the collective murder of an arbitrary victim evolved into sacrificial rituals, and then every aspect of ritual and religion. Ritual evolved into myth, and myth evolved into tragedy and all theatre. Just like the original murder, theatre delivers what Aristotle called catharsis, an expulsion of negative elements.

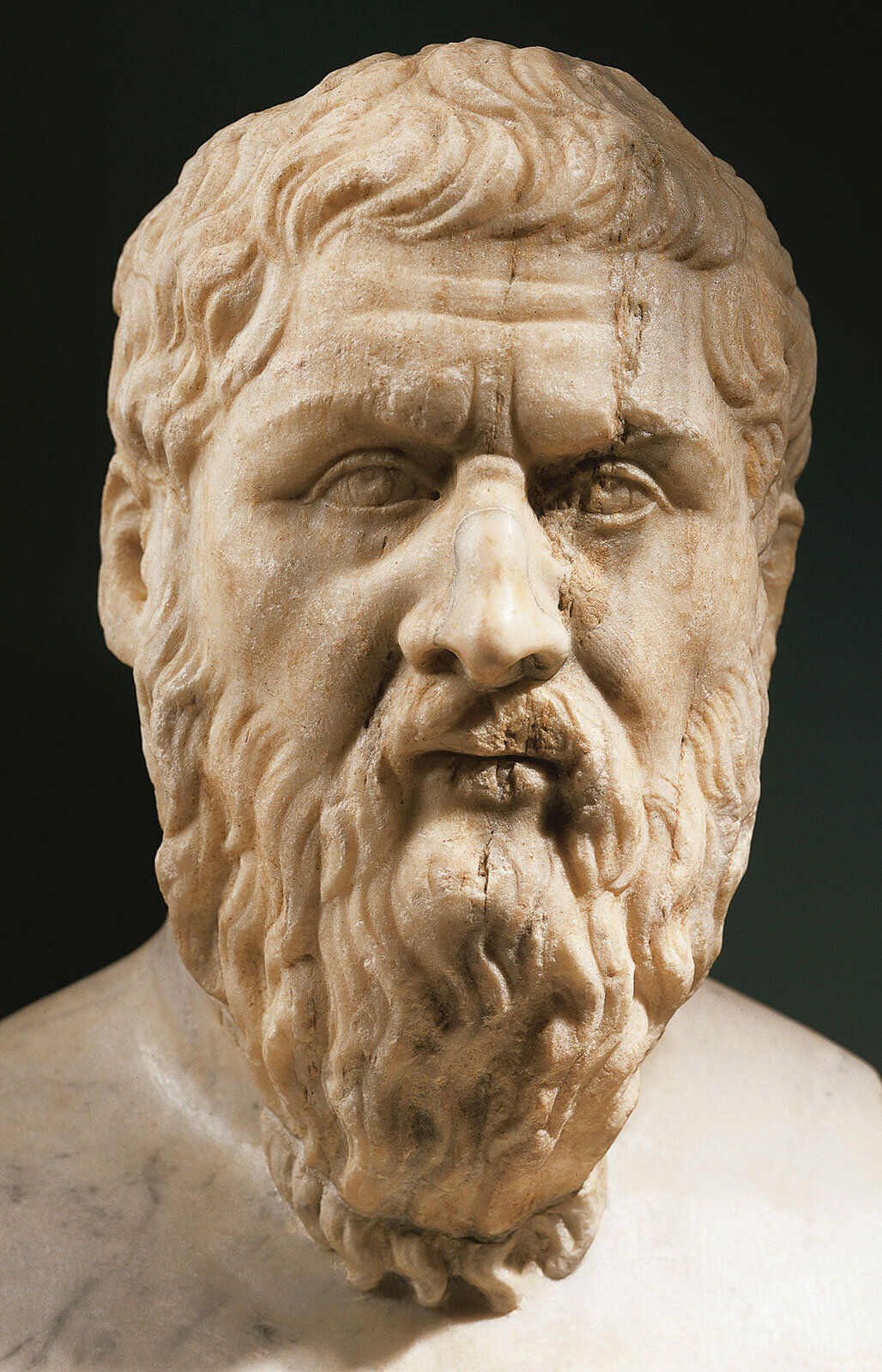

Girard found it very significant that Plato, the founding father of classical philosophy, hated theatre. Plato thought of it as inflaming emotions rather than promoting reason. In Girard’s interpretation, Plato had a strong archaic intuition of theatre as a sacrificial ritual, whose violence always carried a potential to destabilize the community. However, what Plato failed to see was that the limited violence of the theatre is necessary to diffuse the threat of violence spilling beyond the stage and engulfing the entire society. This diffusion, this expulsion of aggression is precisely what Aristotle recognized as the catharsis that is helpful, if not necessary, for maintaining social order.

Plato was a true-believing philosopher convinced that through reason alone man can achieve perfect peace. Ritual violence or any of its sublimated forms were not necessary. His attitude towards theatre is an exact analogue to the modern academic attitude towards religion: through science alone man can achieve happiness, and faith is unnecessary and even harmful. Yet, for reasons of human nature, both Plato and his modern descendants, the academics, have failed to convert the masses around them.

Human beings cannot live on reason alone because human beings are mimetic. Our struggle is not solely about understanding; it is about desiring. Our minds are capable of logic, but our minds are also wired to imitate, and we cannot imitate anything but other people. Through mimesis we connect to other humans and derive our own identities; without it, we would be unbearably alone. Without it, we would not even be conscious. But it is through imitation of others that we obtain our desires, and this inevitably leads to envy and conflict. There is evidence that properties of the brain that enable imitation are the same properties that enable learning and intelligence. The human propensity for conflict is thus inseparable from the human drive for knowledge.

This essential argument of mimetic theory corresponds to religious doctrines of fundamental human sinfulness. Plato and intellectuals after him fail to recognize just how deeply the propensity for conflict is rooted in human nature. They tend to view it as a sort of skin-deep tumour that should be easy to remove if only the patients would be willing to submit to a good surgeon. Intellectuals are perpetually scandalized by how irrational and ignorant the society around them is.

On the other side, to those who have made their peace with the ways of the world, intellectuals appear as intelligent but naïve, or as modern academic parlance would have it, as having high IQ but low EQ, or emotional intelligence. Intellectuals are nerds, well-meaning and useful soldiers of progress who hold overly optimistic views of human nature, and consequently often end up disappointed, unappreciated, or exploited.

The Western intellectual tradition originated in classical Athens when philosophy presented itself as an institutionalized alternative path for transcendence. Man could attain godliness, or virtue, not through ritual worship of God, but through the cultivation of the mind and acquisition of knowledge. Yet both the old forms of worship and the new path to enlightenment involve catharsis, or the expulsion of evil. While in religion the scapegoat is typically a character who one way or another transgresses sacred boundaries, in philosophy evil takes on the impersonal form called ignorance.

Philosophy and later all academia can thus be placed in the evolutionary line of scapegoating mechanisms, in the narrow sense of mechanism whose social role is to expel evil. This line begins in the archaic lynching of arbitrary victims, which then takes on the form of substitutionary violence through sacrifice and all archaic ritual, to which are later added religious and legal codes, and finally, there comes philosophy - the expulsion of evil through expulsion of ignorance.

In philosophy, and later science, there are not bad people really, only wrong ideas. The dichotomy between good and evil becomes identified with that between knowledge and ignorance. The basis and inspiration for this faceless, impersonal interpretation of our life is the inanimate universe. Plato draws on the already old tradition of natural philosophy, and especially on astronomy and mathematics, to argue that the universe is by default imbued with harmony and reason. Violence and conflict are some sort of an aberration, a work of an inferior Demiurge. The good creator has already created a peaceful, differentiated universe, giving a unique and blessed role to every star in the firmament. People only need to raise their eyes to this highest harmony, and in a philosophical equivalent of mimesis, they would absorb the logos emanating from it and achieve peace.

Besides natural science, the philosophical tradition founded by Plato was founded on the work of his teacher Socrates. The latter famously had no interest in studying nature, arguing that there is no point to it when one knows so little about man. In his questioning of established social order, Socrates wobbled its sacrificial pillars, all those dichotomies of good and evil that are in reality founded on unanimous violence against arbitrary victims, be they national enemies, slaves, women, sacrificial animals, etc. Socrates truly is a sort of a pagan figure of Christ in this regard. It was in this weakened cultural order that Plato introduced philosophy as the new path to transcendence, going beyond his master’s merely agnostic and non-violent questioning of old ways.

The Platonic ideals that comprise the perfect universe have always been at the heart of Western intellectual, or humanist, tradition. They reverberated in the Age of Enlightenment, with its ideas of the innate goodness of man and of ignorance being the root of all evil. They end up denying violence the fundamental role that in reality it does play in human affairs. From there, they deny that ritual, a controlled form of cathartic violence, plays a legitimate role in society. When René Girard criticizes widespread Platonism, I believe that by it he means precisely this assumption of the universe harmonized and differentiated by default, and by extension of an intrinsically harmonized man who does not need to repair his basic nature.

To Plato, theatre seemed to do nothing but stir up dangerous emotions, and to Enlightenment humanists, old hierarchies seemed to do nothing but oppress people. They were probably both right because they both lived in the decadent stages of their respective cultures. For the humanists, the solution to man’s misery was not in limiting desire, as religion would have it, but in satisfying them. It was concluded that the problem was not in the mediation of desire, but in its objects – to wit, the objects were unwieldy, and there was not enough of them. With the Renaissance, modern science and technology were born to solve these problems. They took the central position in culture, displacing former emphasis on managing human relations. The modern dismissal of mimetic desire is equivalent to Plato’s dismissal of theatre. In both cases, we have intellectuals feeling queasy about raw passion. We have nerds.

The modern focus on objects and their supposed intrinsic value, accompanied with the refusal to acknowledge the destructive power of desire, has given rise to the great modern tragedies of social experimentation, as well the comedy centred around nerds. It has resulted in modern intellectuals dismissing mimetic behaviour as an aberration to be blamed on repressive social structures.

All modern social doctrines suffer from the erroneous assumption that people have fixed desires for objects with intrinsic value. They are all materialist, in other words, and materialism lends itself well for the empirical endeavour: materials can be manipulated and measured. Indices such as gross domestic product, life expectancy, or energy consumption can be used as evidence of progress. Yet, the materialist ignorance of mimesis often leads to disaster.

Marxism, that great materialist doctrine of modern society, assumes that a person desires material possessions in and of themselves. Formally, it completely ignores the plain fact that humans work to differentiate from one another and that without differentiating incentives there can be no economy. Underneath the surface, Marxists also ignore their own materialistic envy as the driver of their convictions. Marxism is driven by the negative mediation of envy, but as this is embarrassing to admit, a society of supposedly authentic Marxists slides into a peculiar form of self-induced naïveté. Underneath the surface, negative mediation remains, and there inevitably arise cynical leaders who will exploit it in pursuit of personal power.

Marxism today probably presents the best textbook example because its contradictions are so obvious. Societies based on Hobbesian social contract tend to fare better because they place less trust in human nature - “Homo homini lupus”. However, they too assume that desire is authentic, and Ango-Saxon capitalist societies too tend to experience mimetic crises, in their case based around the failed transcendence of private property. The various doctrines based on superiority, whether racial, national, or genetic, are rife with false transcendence that they attempt to fulfill through resentment if not open violence against the supposedly inferior, but never with any success.

There is also a comedy that plays out through mistaken identities and misplaced struggles. The scientist who focuses on objects and ignores passions may appear as a saint who has risen above the lusts of the world and reached into the Platonic firmament with its perfect harmonies. In actuality, the scientist may simply be emotionally incapacitated, what today we call autistic. Or, more likely than not, his chief passion may be a type of sublimated will to power peculiar to the intellectual, what Friedrich Nietzsche talked about. The nerdy scientist may be riddled with lusts, but he doesn’t dare declare them in the open. He prefers to hide them and wait for his moment of materialist conquest.

The charade of materialist conquest plays out everywhere around us, and everywhere underneath it, one can detect the same mimetic forces that have always moved human society. Silicon Valley companies are staffed with armies of faceless engineers working on incremental improvements to IT technology. Their bosses, the heroic Tech Founders, are often thought of as scientific geniuses, but their actual brilliance lies in their ability to appeal to the emotions of consumers, or when they don’t have many consumers, to investors. Bill Gates, Steve Jobs, Mark Zuckerberg, Elon Musk – they don’t sell us merely useful tools, they sell us visions of transcendence.

There are many corners of modern society that have not fallen victim to the materialistic ignorance of human nature, but materialism is everywhere yielded to as a sort of official religion. For example, the advertising industry is all about emotional appeal. Advertising departments in their focus on the human element are exact complements to tech departments. The Mad Men TV series shows executives cynically exploiting the emotional weaknesses of consumers while selling them material progress. As advertising becomes more of an academic discipline, Mad Men are replaced by Math Men [1], creating again an aura of scientific respectability. Yet, as the latest scandals with social media companies show, what math men really do is create algorithms to mimetically manipulate the desires of users. Could it be that social media will be the first technology that will reveal mimesis rather than distract from it?

Of all the professions, it is in modern academia that the denial of mimesis must remain the strongest. An academic lives and dies by producing original research, and academia as a whole has become immensely powerful by endlessly multiplying objects of study. As mimetic theory undermines both originality and objects, it is easy to see why academia, at least in its current incarnation, would be so averse to it. Ironically, this willful ignorance of mimesis among academics makes them especially susceptible to it.

Academia is an amplified mimetic environment because it features young, impressionable minds eager to learn and to compete in learning, and professors in desperate need of disciples. In this light, the much-repeated academic mantra for open-mindedness no longer seems like it promotes critical thinking; rather, it sounds like words to induce hypnosis. Far from being exemplars of disinterested enquiry, the modern academic is in a frantic battle to differentiate himself against his rivals. There is so much research and theorizing going on that he is forced into ever more obscure fields and outlandish theories. With legions of students also looking for transcendence, such theories can nevertheless precipitate mass support.

The more anyone denies the true, mimetic nature of their desire, the more they fall prey to it. This is the grand lesson of great literature, as explained by Girard in his book Deceit, Desire and the Novel. As academia drifts ever further in this denial, it produces more and more neurotic graduates. To obtain mastery of oneself, one is better served with disciplines that openly acknowledge the mimetic struggle, of which I will mention athletics and arts.

Our triangle of desire features us, our model and rival, and the object of desire. This triangle endlessly torments our consciousness. Sports create transcendence by giving us a path to victory over rivals, while art allows us endless horizons to explore the object. Both sports and art bring us closer to our true nature; through them, we explore and confront our desires and can achieve a certain level of managed peace with them. The success of both athletes and artists immediately produces an aura of self-mastery in their authors, giving them a magnetic charisma that attracts the masses to whom they become idols (external models). The same cannot be said of modern intellectuals, whose pursuit of transcendence always carries a whiff of dishonesty.

When intellectuals do become rock stars, it is always through attuning their work to the zeitgeist, to the contemporary consensus of desire. Cometh the hour, cometh the man. Even lectures on the purest theoretical physics are imbued with the language of desire. They begin and conclude with monologues on our place in the universe, on the marvels of nature, on time, intelligence, infinity. Even the driest essay is performance art, carefully choosing what to reveal and what to hide, carefully invoking and courting the desires of the reader. Those who do not recognize this primacy of desire in every human endeavour inevitably end up working in the dark as it were, talking to nobody.

Read more in the book Catharses.

[1] https://www.nytimes.com/2015/04/04/business/media/mad-men-and-the-era-that-changed-advertising.html