We Are Equal: Always and Never

Why is it that historically, most cultures have nurtured the principle that human beings are sacrosanct and essentially equal while practicing every form of oppression, from slavery to all kinds of discrimination?

For example, how come the American founding fathers themselves wrote in the Declaration of Independence that all men are created equal, while they owned slaves? Or how come all those Ancient Athenian philosophers with their noble humanistic principles turned a blind eye to slavery in their society? Or we can talk about Medieval Europe, whose elites were Christian while oppressing serfs. This paradox existed always and everywhere, and it persists to this day.

The superficial answer to this question is “hypocrisy.” People pay lip service to some ideal to cleanse their conscience, but in their everyday life, they take unfair advantage of their fellow human beings. But to whom were they paying lip service? Today, such a contradiction in conduct would require hypocrisy, because the public would not stand for it, but throughout most of history, the public was fine with it.

There must be something more to it. Traditional cultures did not see any contradiction. To understand why, we must appreciate their understanding of the sacred (in the anthropological, Girardian sense). To these cultures, differences between human beings were insignificant when compared to the difference between frail mortals and the terrifying, all-powerful gods.

To traditional cultures, the difference between a blessed life and all kinds of hell on earth was the difference between getting on the good side of a god and getting on his bad side. Those who lived a good life were rewarded it by heaven, and those who were down and out did something to offend god, so they deserved their accursed fate.

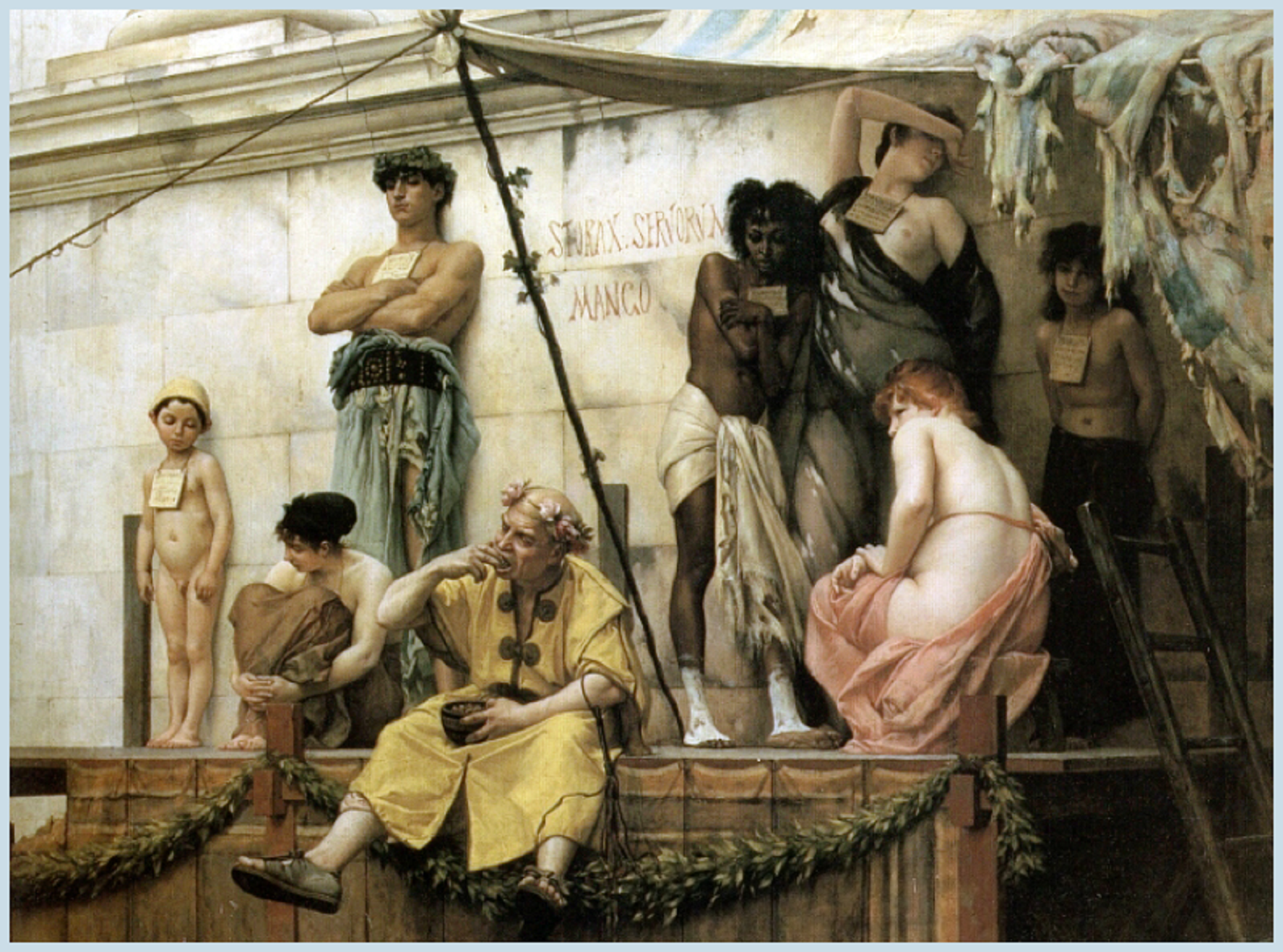

This was why even the most humanist of Ancient Romans could sleep well at night while their society lived off slavery and enjoyed gladiatorial games. It’s not that the slaves or the gladiators were seen as essentially inferior; rather, they were seen as accursed: they had committed some unforgivable offence to some god and were paying for it with their bad fortune.

In our modern culture, such justifications for oppression no longer work. We no longer believe in the violent sacred. You cannot justify social oppression in a liberal democracy by saying that the victims are cursed. This is a good thing, but it creates a new problem: how do we justify differences now?

We cannot live in a society where everyone is the same. We don’t want to be the same; we want to be appreciated as unique and special. Total sameness is nothing other than total mimetic crisis, a nightmare in which everyone is everyone else’s evil twin. Such a situation would lead to chaos, to conflict of all against all. So we need to have differences, but we are not sure on what basis to justify our differences. Unlike the ancients we can’t dump it on some angry god: “The reason why you’re below me is because God likes me more than you.”

Many a modern social doctrine attempts to resolve this problem. Social Darwinism, social contract, Marxism – they all try to establish some new theory of differentiation in the wake of the recession of the violent sacred.

You may also put forward the idea of meritocracy as the obvious solution to the need to differentiate. Everyone gets tested for a skill, and the best candidates get the role. But the notion of differentiation, of getting everyone to stay put in their social role, is more than allocating jobs based on merit. If you truncate identity to performance, you get just another unstable hell of unhinged competition. Also, will most people who do not come out as number one in some measure of success accept their position as inferiors? Do we as people accept that performance is all there is to our value as human beings?

Most recently, in liberal Western democracies, there has been this social project of attempting peaceful differentiation based on everyone’s unique desires. We are all equal, but we are all different. The way for a person to carve out that unique place for themselves is to dig deep into who they really are and what they really want, and they will come out as a special and inimitable individual. Society is to give maximum free play to the individual expression of desire, and it will achieve maximum differentiation and harmony.

The infinite proliferation of new identities we are experiencing in liberal democracies today is the attempt at this brave-new-world differentiation. Those who discover new identities for themselves are hailed as the pioneers and heroes of a radically freer world. But is it working? Will it work? No.

The great error of differentiation by unique desires is that our desires are not unique. This is the central argument of mimetic theory. Our desires are imitated. They are subject to fads. They are fickle. They are not innocent: we want what other people have.

And what the current project of differentiation by radically authentic desire achieves is nothing but radically unstable runaway loops. No one is more susceptible to losing a sense of their true self than those trying desperately to invent a new self. The political sanctification of uniqueness is creating a politics of brainless, sheepish surrender to every and any new fantasy. This, in turn, is preparing the grounds for authoritarianism.

True progress will require our recognition that our desires are not innocent. This was perhaps the most universally recognized precept of any traditional society. Yet, it’s a precept that we moderns have discarded. For us to get along and move along, we must master and manage our desires (we can never get rid of them). Not let them loose to take over our common sense. However, it would be regressive to return to a sacred that violently shoves people into their social roles. Indeed, the idea of the violent sacred was itself the oldest copout of desire: it was an excuse for oppressing others.

So, in a nutshell, true progress lies in us taking responsibility for all our desires, all of which can easily lead to conflict and violence.